Published on and written by Cyril Jarnias

Published on and written by Cyril Jarnias

Long reduced to a few clichés about its crisis, Venezuela remains one of Latin America’s most spectacular countries for those interested in vast landscapes, indigenous cultures, and history-laden cities. From Angel Falls to the coastal desert of Coro, from the coral islands of Los Roques to the Andean peaks of Mérida, the country concentrates a diversity of landscapes that is hard to match. By exploring its national parks, deltas, and colonial towns, one discovers a territory where nature and culture are in constant dialogue.

This selection highlights the most representative sites in Venezuela, which alone justify a trip. They are all iconic, accessible via minimal tourist infrastructure, and representative of the country’s natural or historical wealth. The goal is not to be exhaustive, but to focus on the essentials.

Angel Falls and Canaima National Park

It’s hard to talk about tourism in Venezuela without starting with Angel Falls, the world’s highest waterfall. Nestled in the heart of Canaima National Park, in the Gran Sabana region, this 979-meter-high cascade, with an 807-meter free fall, seems to spring directly from a vertical wall of Auyán-tepui, one of those mysterious table-top plateaus typical of the south of the country.

Angel Falls gets its name from the American pilot Jimmie Angel, who was the first to fly over it in the 1930s. However, the region had long been known to the Pemón, an indigenous people who inhabit these high-altitude savannas and call the waterfall Kerepakupai Merú. This indigenous name is one that some political figures have tried to bring back into prominence, without the international name Angel Falls disappearing altogether.

To reach an isolated waterfall in the heart of the rainforest, you must first travel to the village of Canaima by small plane from cities like Caracas. Then, a several-hour motorized canoe (curiara) crossing is required to travel up the Carrao and Churún rivers through pristine jungle, with no road access.

The final part is done on foot, along a trail of about half an hour to the viewpoint at the foot of the falls. During the rainy season, from June to November, the curtain of water is so powerful that a cloud of mist envelops the valley. In the dry season, from January to April, the waterfall may shrink to a thin stream, but access to the pool for swimming is often easier and the sky clearer for photography.

The site’s isolation preserves it but imposes certain conditions. Accommodation is provided by Pemón villages, camps, or small lodges, with local guides mandatory. Electricity is available only for a few hours each evening, internet connection is sporadic, and it is essential to have cash in foreign currency for transactions, as the local currency is very volatile. This UNESCO-listed park, dominated by ancient tepuis, offers an experience in the heart of preserved nature.

The Gran Sabana and the Tepuis: Roraima, Kukenán, and Others

Around Angel Falls, Canaima National Park extends over some 30,000 km², an area comparable to Belgium. Two-thirds of this territory is covered by tepuis, these immense sandstone mesas that rise like natural fortresses. Among them, Mount Roraima is arguably the most famous. Located on the border with Brazil and Guyana, it peaks at about 2,600 meters, protected on all sides by 400-meter-high cliffs.

In the 19th century, he discovered a natural ramp allowing him to reach the summit of Roraima without technical climbing, guided by the Pemón. Since then, the hike to its “table” has become a trekking classic, accessible from Santa Elena de Uairén and the community of Paraitepuy.

Everard Im Thurn, British botanist

On the summit platform, the landscape literally evokes a lost world: labyrinths of rocks sculpted by erosion, natural pools nicknamed “jacuzzis”, valleys covered in quartz, dark ponds, geological curiosities like “La Ventana” or “Maverick Rock,” the highest point. The isolation of this environment has fostered the evolution of endemic species: carnivorous plants, ferns, bonnetias, small amphibians like the famous Roraima toad that rolls into a ball to tumble down rocky slopes.

The Gran Sabana as a whole—grassy valleys, waterfalls like Aponwao (Chinak Merú), rivers tinted red by minerals—makes up a sort of showcase of the most spectacular aspects of the Guiana Shield. It is also a sensitive zone, exposed to threats from illegal gold mining and infrastructure projects contested by local communities.

To give an idea of the scale and singularity of this region, we can summarize some key data in a table.

| Site / Feature | Main Characteristic | Approximate Key Data |

|---|---|---|

| Canaima National Park | 2nd largest park in the country, UNESCO-listed | ~30,000 km² |

| Angel Falls | World’s highest waterfall | 979 m high, 807 m free fall |

| Mount Roraima | Iconic tepui, at the triple border | 2,600 m altitude, summit ~31 km² |

| Gran Sabana | Region of savannas and tepuis in the southeast | Included in Canaima, millions of hectares |

The Mérida Cable Car and the Venezuelan Andes

At the other end of the country, in the western Andes, another world record attracts travelers: the Mérida Cable Car, also called Mukumbarí. Connecting the university city of Mérida to the heights of Sierra Nevada National Park, it holds the title of the world’s highest cable car, with a terminus at 4,765 meters above sea level at Pico Espejo. It is also one of the longest, with a total route of 12.5 kilometers divided into four successive sections.

The cable car, completely renovated in the 2010s, departs from Barinitas station (1,600 m) and serves the La Montaña, La Aguada, and Loma Redonda stations. During the ascent, the landscape evolves from cloud forests to high-altitude páramos, dominated by frailejones, Andean plants adapted to the cold with their fuzzy covering.

From the cabins, you can take in the Mérida valley, the gorges of the Chama River, and neighboring peaks like Pico Bolívar, the country’s highest point at nearly 4,978 meters. Upon arrival, the Pico Espejo station offers panoramic platforms, some dining services, and a small museum on the history of the cable car. The effects of altitude are noticeable: it’s not uncommon to have to walk slowly, as the air is thin.

Year the historic system was shut down for safety reasons, prior to its complete replacement.

The combination of height and distance makes the Mukumbarí a sort of condensed version of the Venezuelan Andes accessible in a few hours. You go from the urban atmosphere of Mérida to the snowy ridges of Sierra Nevada National Park effortlessly, making it one of the country’s most spectacular and well-organized tourist sites.

To place this cable car in relation to other major sites, we can compare some figures.

| Attraction | Type | Approximate Maximum Altitude / Distance |

|---|---|---|

| Mérida Cable Car | Andean cable car | 4,765 m at Pico Espejo, 12.5 km journey |

| Pico Bolívar | Highest summit | ~4,978 m altitude |

| Pico Naiguatá (Cerro El Ávila) | Summit above Caracas | ~2,765 m altitude |

Around Mérida, other sites complete the picture: Sierra Nevada National Park itself, the Sierra de La Culata, the Llano del Hato astronomical observatory, the city’s markets, and its botanical garden. But for a first visit, the ascent to Pico Espejo remains the unmissable experience.

Los Roques: The Picture-Perfect Caribbean Archipelago

A radical change of scenery with the Los Roques archipelago, north of Caracas. Here, no mountains or tepuis, but a constellation of islands, islets, and sandbanks set on a vast turquoise lagoon. This ensemble of more than 300 emerged formations is encircled by two long reef barriers that form a sort of giant atoll, protected as a national park since the 1970s.

The inhabited heart of the archipelago is the island of Gran Roque. You almost always arrive by small plane from the capital or other coastal cities: the airstrip, recently expanded, is just a few minutes’ walk from the village. With its sandy streets, its low houses transformed into charming posadas, and its lighthouse perched on a 130-meter hill, Gran Roque serves as a base for daily excursions to other islets.

Take advantage of daily excursions in peñeros, the local boats, to discover surrounding islets like Francisky, Madrisquí, Crasquí, Noronquí, and Cayo de Agua. These trips consistently offer white sand beaches, translucent waters ideal for snorkeling near coral reefs, and sometimes lunch at a wooden beach restaurant serving grilled fish and seasonal lobster.

Los Roques has long been renowned for the quality of its reefs, among the best preserved in the Caribbean: about sixty coral species have been identified, more than 280 fish species, a great variety of sponges, mollusks, and crustaceans. The Thalassia seagrass beds serve as nurseries for young fish and sea turtles. Four species of threatened turtles also come here regularly to lay eggs: green turtle, loggerhead, hawksbill, and leatherback, especially on Dos Mosquises Island, which also houses a dedicated research and conservation center.

The archipelago is home to a great diversity of seabirds (frigatebirds, boobies, terns, seagulls, brown pelicans, flamingos) that populate the sandbanks and mangroves. It is recognized as an Important Bird Area by BirdLife International.

To grasp the ecological importance of this string of islands, some values are telling.

| Natural Feature | Order of Magnitude / Characteristic |

|---|---|

| Number of islands / islets | ~350 formations (islands, cays, sandbanks) |

| Land area | ~40.6 km² |

| Marine park area | Approximately 220,000 ha (nearly 900 km²) |

| Central lagoon | ~400 km² of shallow waters |

| Coral species | ~60 to 70 recorded |

| Bird species | ~90 species, including ~50 North American migrants |

Touristically, Los Roques operates according to a particular model: the vast majority of visitors stay in the posadas of Gran Roque, often on a full-board basis, and organize sea trips, borrowing of masks and snorkels, or rental of diving and kitesurfing equipment with their hosts. A few sailboats also offer cruises with overnight stays on board. Camping is possible but very regulated and marginal.

Protected since the 1970s, the archipelago is subject to strict regulations regarding fishing and visitation. A limited number of professional fishermen are allowed, some iconic species like the conch are subject to moratoriums, and the most sensitive areas are reserved for scientific research. Despite pressures (coral bleaching, lack of surveillance resources), the whole is still considered one of the last relatively intact major reef systems in the Caribbean.

Morrocoy: Mangroves, Beaches, and Birds of the Central Coast

On the mainland coast, a few hours’ drive west of Caracas, Morrocoy offers a more accessible but just as photogenic version of the beach-coral reef combination. This national park, located in Falcón State, covers approximately 320 km² of land and sea in the Gulf of Triste. It encompasses low hills, coastal lagoons, extensive mangroves, seagrass beds, and a myriad of cays.

The main entry points to Morrocoy National Park in Venezuela are the small coastal towns of Tucacas and Chichiriviche, which concentrate tourist infrastructure like marinas and agencies. Exploration is done by boat, often adapted fishing boats, to navigate between the different islets (cayos). Cayo Sombrero, with its palm trees and crescent-shaped beaches, is the most popular and heavily visited destination. For more tranquility, sites like Los Juanes (a shoal), Cayo Sal, Cayo Peraza, or Playa Mero offer calmer atmospheres.

One of Morrocoy’s great assets is the mosaic of mangroves bordering its channels. These amphibious forests harbor a remarkable avifauna: flamingos, roseate spoonbills, scarlet ibises, herons, pelicans, frigatebirds, parrots, etc. This ensemble has earned the park the label of an Important Bird Area. Underwater, coral reefs and seagrass beds host tropical fish, crustaceans, sea turtles, and sometimes even manatees and dolphins, although the latter are more elusive.

The archipelago’s environment, more vulnerable than that of Los Roques, is suffering from reef decline due to mass tourism, unregulated construction, and pollution from boats. Authorities are trying to reconcile tourism and conservation through regulation, limiting activities, and raising awareness.

We can summarize the main differences between the country’s two major marine parks as follows:

| Criterion | Los Roques | Morrocoy |

|---|---|---|

| Main Access | Light aircraft (Caracas → Gran Roque) | Road (Caracas → Tucacas / Chichiriviche) |

| Type of Visitors | More selective, focused on stays in posadas | More mass tourism, strong national clientele |

| Main Environment | Open offshore atoll, deep reefs | Coastal bay, lagoons, mangroves, cays |

| Dominant Accommodation | Posadas, sailboats | Hotels, posadas, rentals, day trips |

| Environmental Pressures | Fishing and resource management | Urbanization, pollution, overcrowding |

For travelers, Morrocoy represents a more flexible option in terms of budget and logistics, while still allowing you to enjoy surprisingly beautiful beaches and observe rich wildlife, especially during boat rides at sunrise or sunset in the mangrove channels.

The Orinoco Delta: Immersion with the Warao

In the east of the country, where the Orinoco, one of South America’s largest rivers, flows into the Atlantic, extends an amphibious world of more than 30,000 km² made of river branches, channels, swamps, and flooded forests: the Orinoco Delta, also called Delta Amacuro. This aquatic labyrinth, larger than Belgium, is home to the Warao people, whose name literally means “canoe people.”

For centuries, the Warao’s life has been intimately linked to the waterways and the moriche palm, which provides them with food, drink, fibers, and building materials. Their traditional stilt houses, with palm roofs and no walls, line the channels. Their movements are mainly by canoe. Their water villages, observed by early European explorers, are said to have inspired the name Venezuela by comparison with Venice.

Tourism in the delta has developed in a very limited way, around a few isolated lodges accessible by boat from embarkation points like San José de Buja or inland towns like Maturín. Structures like Orinoco Eco Camp or Orinoco Delta Lodge have been designed to incorporate some Warao architectural codes (palafitos, leaf roofs, hammocks), while offering a minimum of comfort: beds with mosquito nets, common areas, showers, sometimes electricity to charge camera batteries.

Activities offered include canoe trips to observe wildlife (howler monkeys, sloths, river dolphins, caimans, toucans), night walks, piranha fishing, forest walks with a Warao guide on medicinal plants, visits to communities to discover handicrafts (basketry, jewelry), and birdwatching of aquatic birds (hoatzins, herons, ibises, kingfishers).

The delta is one of the places where you feel most strongly the Amazonian dimension of Venezuela: dense jungle, abundant insects, changeable weather, a sense of being at the end of the world. It is also a fragile ecosystem, subject to pressures: animal and timber trafficking, increasing poverty of local populations, effects of the national crisis. Medical NGOs, like Doctors Without Borders, have carried out health programs there, a sign of the difficulties in accessing care.

For travelers willing to accept a certain degree of rusticity, the Orinoco Delta nonetheless offers an experience hard to reproduce elsewhere: that of a stay in the midst of almost intact nature, sharing a few days of the daily life of a people who have, to this day, adapted their way of life to an extreme environment.

Mochima National Park: Between Mountains and the Caribbean Sea

Still in the east of the country, but further north, Mochima National Park forms a long strip of protected coastline between Puerto La Cruz and Cumaná, over nearly 50 kilometers of coast. Created in the 1970s, this marine park covers nearly 95,000 hectares, including 32 islands and a portion of the coastal mountain range that literally falls into the sea.

The region features varied relief, alternating arid hills covered with cacti and humid valleys with tropical vegetation. The coastline offers white sand beaches, islands, mangroves, and coral reefs, with about sixty sites identified for diving and snorkeling.

The villages of Santa Fe or Mochima often serve as starting bases, with simple posadas, fish restaurants, and the possibility of renting boats for the day. Excursions combine swimming, dolphin watching (especially near Isla de Plata), exploration of sea caves like Cueva del Pirata, stops at iconic beaches like Playa Colorada, recognizable by its reddish-tinged sand, or Playa Blanca, very popular with families.

More than 200 species of fish populate the archipelago’s waters, illustrating its remarkable biodiversity.

As elsewhere, park management faces challenges: presence of villages within the boundaries, infrastructure projects like roads or gas pipelines, limited resources for surveillance. Yet, for many travelers, Mochima remains the very image of an accessible “little Caribbean paradise”: relaxed atmosphere, welcoming inhabitants, favorable weather much of the year, opportunities to combine beach, hiking, and discovery of local culture.

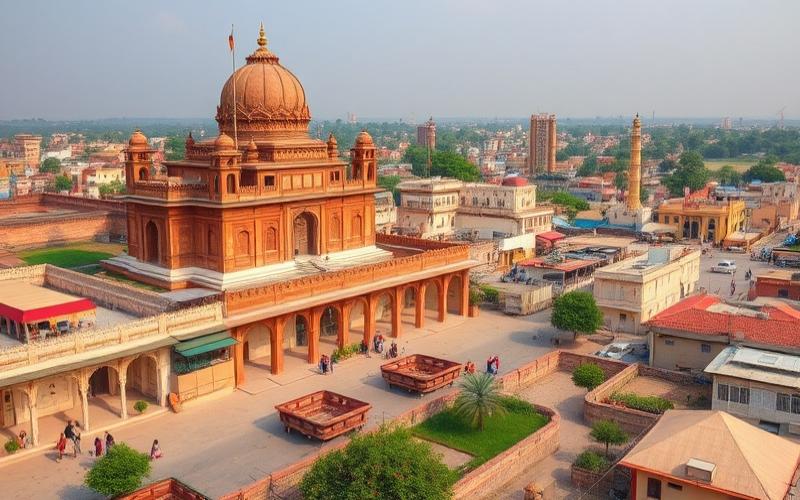

Coro and Its Port: Colonial Heritage on the Edge of the Desert

Venezuela is not just its natural landscapes. On the coast of Falcón State, the city of Coro and its port of La Vela constitute one of the country’s most important heritage ensembles. Founded in 1527 as Santa Ana de Coro, the city is the second oldest in Venezuela, after Cumaná. It was successively the bridgehead for German ambitions in South America, the first capital of the Captaincy General of Venezuela, and the seat of the first bishopric on the South American continent.

Listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1993, Coro and its port owe their exceptional value to a remarkably preserved urban fabric of earthen architecture. Houses in bahareque (a mix of mud, wood, and bamboo), rammed earth walls, adobe bricks, wooden frameworks: the palette of construction techniques reflects a skillful blend of local, Spanish (notably Mudejar), and Dutch influences, the latter arriving from the neighboring islands of Curaçao and Aruba.

Discover the architectural and cultural treasures of Coro, a UNESCO World Heritage city, through its emblematic buildings.

More than 600 ancient and colorful buildings, with windows adorned with wrought iron grilles imported from Andalusia.

One of the oldest churches in Venezuela, whose construction began in the late 16th century.

The San Francisco Convent and the Casa de las Ventanas de Hierro illustrate the city’s past wealth.

Historic buildings house museums, like the Balcón de Bolívar or the Alberto Henríquez Art Museum in the former synagogue.

The historical dimension is not limited to the colonial period. It was from La Vela that the expedition of Francisco de Miranda departed in 1806, carrying the tricolor flag that would become the model for the flags of Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador. It was also around Coro that slave rebellion movements were born and, later, the Federal War, which deeply marked the country’s political history.

The immediate surroundings offer varied landscapes: to the north, Médanos de Coro National Park presents golden sand dunes sculpted by the winds (giving the city its name). To the south, Sierra de San Luis National Park offers mountains, spectacular caves like Haitón del Guarataro, and birdwatching. Further west, the Urumaco site is an important fossil deposit.

Coro also illustrates the fragility of earthen heritage faced with exceptional rains, rising water tables, and poorly controlled urban planning. Following episodes of abnormally intense rainfall in the 2000s, many buildings were damaged, prompting UNESCO to inscribe the site on the List of World Heritage in Danger. Management plans, emergency funding, and mobilization of local communities have been put in place to try to halt the degradation.

A Mosaic of Sites, the Same Complexity

The sites mentioned — Angel Falls and Canaima, Roraima and the Gran Sabana, the Mérida Cable Car, Los Roques, Morrocoy, the Orinoco Delta, Mochima, Coro and La Vela — are just a sample of what Venezuela can offer. Together, they cover an impressive range of ecosystems: tropical forests, high-altitude savannas, Andean mountains, coral reefs, mangroves, deltas, coastal deserts, and colonial cities.

Venezuelan national parks, like Canaima or Los Roques, face constant tensions between conservation and development. The main threats include illegal mining, energy projects, uncontrolled urbanization, overcrowding, and lack of resources for management. Sites like Coro battle erosion, while the Orinoco Delta suffers from the marginalization of indigenous peoples and pressure on its resources.

For the traveler, these sites nevertheless remain places of rare power, provided the country is approached with preparation, caution, and respect. The overall security situation requires getting information from specialized operators, favoring better-managed zones and circuits—Canaima, Mérida, certain marine parks—and going through local guides, often from indigenous communities like the Pemón or Warao. But those who overcome these logistical obstacles find in Venezuela something increasingly rare: the feeling of discovering immense landscapes still largely preserved, and cities where history never really stopped.

Whether you’re drawn to vertiginous waterfalls, mythical plateaus, coral islands, amphibious forests, or the cobbled streets of old cities, the must-see tourist sites in Venezuela map out a country where natural grandeur, cultural diversity, and contemporary complexity intersect. A difficult country, undoubtedly, but unforgettable for those who take the time to immerse themselves in it.

Disclaimer: The information provided on this website is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or professional advice. We encourage you to consult qualified experts before making any investment, real estate, or expatriation decisions. Although we strive to maintain up-to-date and accurate information, we do not guarantee the completeness, accuracy, or timeliness of the proposed content. As investment and expatriation involve risks, we disclaim any liability for potential losses or damages arising from the use of this site. Your use of this site confirms your acceptance of these terms and your understanding of the associated risks.