Published on and written by Cyril Jarnias

Published on and written by Cyril Jarnias

Renovating a property in South Korea, whether you’re a resident or a foreigner, is no longer just a simple “paint job.” Between soaring construction costs, tightening energy standards, the booming home remodeling market, and the growing influence of Korean design, every project becomes a true strategic undertaking. The stakes are no longer just aesthetic: they affect the property’s value, its thermal performance, its rental appeal, and even compliance with sometimes complex regulations.

This guide covers the market context, legal framework, budgets, and design trends, from traditional hanoks to high-tech apartments. It also includes pitfalls to avoid and levers to optimize your investment.

A Renovation Market in Full Transformation

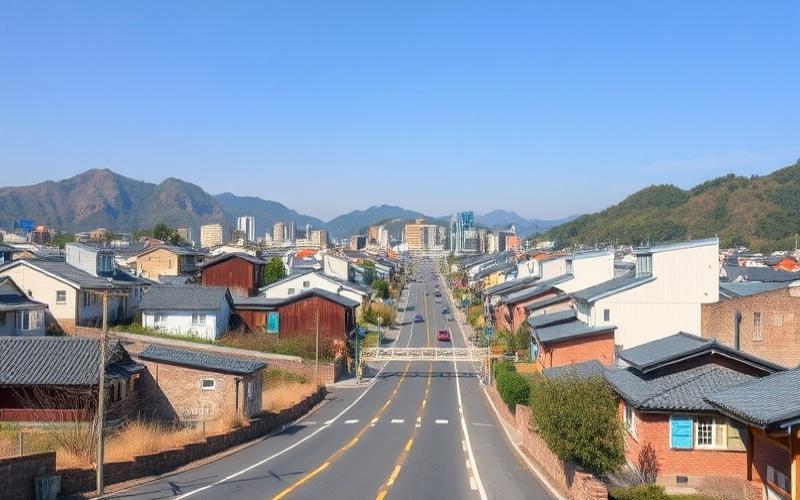

The South Korean real estate landscape is rapidly changing. For a long time, value was primarily found in new construction: large-scale redevelopment projects, residential towers, new neighborhoods. Now, the economic equation has changed.

The construction cost per pyeong (3.3 m²) for small buildings, having more than doubled in five years.

The trend is quantified: the South Korean home renovation market is estimated at approximately $3.45 billion in 2024 and could reach $5.59 billion by 2033, with an estimated annual growth of over 5%. Major renovations already constitute the primary market segment. This surge is driven by urbanization, rising living standards, and a series of public policies focused on energy efficiency and modernizing the existing building stock.

In Seoul, direct construction expenses for maintenance and remodeling reach an average of 8.42 million won per pyeong, an increase of over 12% year-on-year.

In this context, renovation is no longer a last resort: it is a central tool for value creation, reinforced by increasingly strict energy standards and the spectacular rise of contemporary Korean design, widely disseminated by Hallyu (K-pop, K-dramas, etc.).

Understanding the Legal and Administrative Framework

Before breaking down a single wall, you must navigate the regulatory layer. In South Korea, several overlapping laws govern construction and renovation:

– the Building Act, which regulates substantial work on buildings;

– the National Land Planning and Utilization Act, which governs urban planning and land use;

– the Cultural Heritage Protection Act, for listed buildings or those located in conservation areas;

– local ordinances, for example, the City of Seoul’s Building Ordinance.

Most non-trivial projects require a building permit issued by the mayor or district head (Si/Gun/Gu). In some lighter cases (small extensions or limited repairs), a simple notification may suffice.

Renovation, Reconstruction, “Major Repair”: Crucial Distinctions to Master

Korean law doesn’t use the term “renovation” vaguely. The texts, especially presidential decrees, make very precise distinctions:

| Term (free translation) | Essential Legal Definition | Impact on the Project |

|---|---|---|

| Renovation | Demolition of all or part of a building (including at least three load-bearing elements like walls, beams, columns, trusses) and then reconstruction within the same size limits | Treated as a major project, subject to a permit |

| Reconstruction | Reconstruction after destruction by natural disaster or major event, to an equivalent size | High regulatory burden, specific assessments |

| Major repair | Significant repair without extension or reconstruction, but involving demolition of structural elements exceeding certain thresholds | May require a permit, depending on area and scope |

These categories are far from symbolic: they determine the type of authorization needed, the requirement for technical studies, and even eligibility for certain tax regimes or subsidies. For a foreign owner, surrounding yourself with a local architect and, often, a lawyer or consultant familiar with these subtleties is a prudent investment.

The Typical Path of a Project

The standard procedure unfolds in several successive steps, varying slightly based on the nature and scale of the work but generally follows the same sequence:

The construction process in South Korea follows a regulated sequence: start with an initial consultation at the city hall to verify buildability. You can request an official preliminary determination on the project’s feasibility. The building permit application requires plans by a licensed Korean architect and supporting documents like a cadastral extract. The file review involves cross-consultation between public agencies. After the permit is issued, the site must be supervised by a qualified architect and site supervisor, with mandatory inspections by a certified inspector. Before occupancy, a fire inspection is required to obtain a certificate, followed by obtaining an occupancy permit. Finally, building registration at the land registry, with payment of associated taxes, is necessary to finalize the project.

Complexity increases further if the building is in a protected sector or is a listed hanok under heritage laws. In this case, the Cultural Heritage Protection Act imposes additional constraints: materials, exterior appearance, prohibition on demolishing certain elements, obligation to use specialized artisans.

The Surge in Energy Standards: A Lever, Not Just a Constraint

South Korea now considers the building sector a major battlefield in the fight against climate change. The sector consumes nearly 20% of national energy and generates over 60% of greenhouse gas emissions in cities. Hence, an arsenal of standards and incentive programs directly impacts how to renovate.

The BDCES Code and Performance Obligations

The cornerstone is the Building Design Criteria for Energy Saving (BDCES), a national code that merged several former standards in 2001. It is a prescriptive system with mandatory requirements (insulation thickness, window performance, etc.) and recommended criteria. To be compliant, a building must meet all mandatory criteria and obtain a minimum score of 60 points on a 100-point scale.

The highest-performing buildings can benefit from density relaxations (Floor Area Ratio), which concretely grants them the right to build additional floor area. The system provides, for example, exemptions allowing an increase in the permitted floor area as a reward for their energy or environmental performance.

| Energy Performance Score | Associated “Grade” | Bonus Buildable Area |

|---|---|---|

| 70–80 points | 3rd grade | +2% on permitted size |

| 80–90 points | 2nd grade | +4% |

| 90–100 points | 1st grade | +6% |

In a tight market like Seoul, this bonus can weigh heavily on an operation’s profitability.

For projects of a certain size (new buildings over 500 m²), an Energy Performance Index of at least 65 is required, calculable via an online tool provided by the national energy agency. The permit application must be accompanied by an energy conservation plan signed by an architect, a mechanical engineer, and an electrical engineer.

The Era of Zero Energy Buildings and Green Renovation

Beyond the general code, South Korea is pushing the sector toward Zero Energy Buildings (ZEB). A multi-level certification system (grade 5 to grade 1) is being generalized:

– Since 2023, new or expanded public buildings over 500 m² must be ZEB certified;

– Starting June 2025, private residential complexes (apartments with over 30 units, buildings over 1,000 m²) must achieve at least grade 5.

To accelerate the transition, the government has merged the energy rating system and ZEB certification into a single procedure. This change reduces the processing time from about 80 to 60 days. High-performing buildings can benefit from this simplification.

– acquisition tax reductions;

– construction coefficient relaxations;

– long-term low-interest loans to finance energy-efficient equipment (high-efficiency HVAC, LEDs, insulation, renewables).

Targeted programs amplify this effect for renovating existing buildings, notably:

| Program | Targeted Building Type | Assistance Offered |

|---|---|---|

| Green Remodeling Program | schools, public housing, hospitals | subsidy covering 50 to 100% of costs |

| Seoul Building Retrofit Program | private buildings in Seoul | zero-interest loans for efficiency work |

| Voluntary Agreements | major energy consumers | preferential loans, technical assistance, visibility |

For an owner, these schemes are not anecdotal. Opting for high-performance windows, enhanced insulation, or an energy management system (BEMS) can:

– reduce energy bills, particularly sensitive since the nearly 46% increase in electricity prices between 2022 and 2023;

– improve comfort in both summer and winter, crucial in a climate marked by very hot summers and harsh winters;

– enhance the property’s value in a market increasingly attentive to energy performance.

Budgeting Your Renovation: Rising Costs and Finding Room for Maneuver

On the ground, the cost curve is not kind to owners. In Seoul, the average direct price for maintenance or remodeling work exceeds 8 million won per pyeong, and some major residential projects reach or even exceed 10 or 11 million won per pyeong.

Typical Budget Structure

Even though absolute amounts vary by area, standard, and complexity, the expense structure often follows a distribution close to:

| Budget Item | Indicative Share of Total Budget |

|---|---|

| Materials | ~40% |

| Labor | 30–35% |

| Design / Professional Fees | 5–15% |

| Demolition & Site Preparation | 5–10% |

| Permits, Inspections & Taxes | 2–5% |

| Finishes, Furniture, Lighting | 10–15% |

| Contingency | 10–20% |

For a typical apartment project, a contingency envelope of 10 to 15% is often deemed sufficient. For older or technically complex operations (fragile hanok, 1970s structure, mixed-use building), specialists recommend 20%. For a foreigner managing the site remotely, some experts go as high as 20–25% safety margin to absorb currency fluctuations, imported material overruns, or schedule delays.

Common Budgeting Mistakes

Several pitfalls regularly appear in feedback:

Several critical factors can jeopardize a renovation project: underestimating labor costs in a context of rising wages and enhanced safety standards; an imprecise scope of work leading to overruns with every change; the absence of a reserve fund exposing the site to sudden stoppage in case of unforeseen events; and prioritizing aesthetic works (‘pleasure’) over structural operations, which can harm future profitability.

A pragmatic method involves systematically distinguishing essential needs (structure, safety, compliance, thermal envelope, utilities) from wants (premium finishes, designer furniture), then phasing the latter over several years or rental cycles.

Using the Right Tracking Tools

In large-scale operations, professionals move beyond simple spreadsheets to use dynamic project management platforms, capable of:

Optimize and simplify your site coordination with these key features.

Gather and organize all your quotes, change orders, and invoices in one secure location.

Instantly compare projected costs and actual expenses for better budget control.

Facilitate communication and collaboration between architects, contractors, suppliers, and owners, even remotely.

Even for an apartment project, using a digital tracking tool helps maintain control over deadlines, payments, and budget trade-offs.

Facing the Construction Site: Scheduling, Contracts, and Risk Management

Renovating in South Korea also means confronting a highly structured construction environment, with its own practices, contractual clauses, and specific risks.

Selecting Your Partners

The registration of construction companies is governed by the Framework Act on the Construction Industry. In practice, it is recommended to:

– verify the contractor’s official registration;

– scrutinize their project portfolio (references in the same neighborhood, same building type);

– demand complete transparency on cost breakdown (materials, labor, margins);

– opt for a staged payment schedule: limited deposit, interim payments upon milestone validation, final payment after handover.

For large-scale real estate complexes, major construction groups (GS Engineering & Construction, Hyundai E&C, Samsung C&T, etc.) are preferred. For individual apartments or small buildings, it’s better to approach the many design and renovation companies based in Seoul, such as Collectif B, Design Danaham, D’art Design Seoul, Maumm2, or Steven Leach Associates, depending on the desired service level.

Contracts and Liabilities

Work contracts should ideally be modeled on the standard forms issued by the ministry (general conditions for private or public works). They typically include:

– clauses for delay penalties;

– provisions for contract variations in case of unforeseen site conditions;

– a defect liability period varying by element (structure, finishes, equipment), often between 1 and 10 years;

– a retention guarantee mechanism (often 10% of the work price) released at the end of the liability period.

In case of dispute, the law provides specific bodies, such as the Construction Dispute Mediation Committee or the Architectural Dispute Mediation Committee.

For international teams, linguistic and cultural misunderstandings are frequent, particularly regarding the precise meaning of expressions, hierarchical decision-making processes, or perceptions of delays. To limit these frictions, it is recommended to use professional translators and consistently rely on highly detailed plans and specifications.

Remote Management: A Particular Challenge for Non-Residents

More and more investors manage their sites remotely, relying on:

– a local project manager acting as “eyes and ears” on the ground;

– communication tools (regular video conferences, sharing of site photos and videos, weekly reports);

– payments linked to verifiable milestones (dated photos, virtual tours, inspection reports);

– multi-currency accounts and, sometimes, escrow services to secure financial flows.

The main risks to monitor are known: schedule overruns, budget creep, quality decline, poor coordination between stakeholders. Hence the importance of defining clear protocols upfront: frequency of follow-up meetings, decision-maker for arbitration, leeway on material choices.

Renovating a Hanok: Reconciling Heritage, Modern Comfort, and Ecology

Renovating a hanok in South Korea, especially in a historic district like Bukchon or Seochon, is no ordinary renovation. You are dealing with an architectural heritage whose codes date back to the Joseon period, featuring wood structures without nails, earth and stone walls, curved tile roofs, ondol underfloor heating, and hanji paper windows.

A Resilient and Ecological Traditional Architecture

The hanok should not be seen as a designer’s whim. Its principles address very contemporary sustainability challenges:

– wooden structure assembled by mortise and tenon;

– local natural materials (wood, earth, stone, lime, tiles, straw) almost entirely recyclable;

– ondol system for underfloor heating, with significant thermal mass;

– maru space, raised ventilated floor for summer cooling and moisture barrier;

– orientation according to the baesanimsu principle (mountain behind, water in front) to optimize wind flow and sunlight;

– estimated carbon storage capacity of about 92 tons over a hanok’s lifespan, comparable to a large forest area.

The hanok stock in South Korea has declined from over a million units to just a few thousand.

The Concrete Challenges of Hanok Renovation

On the ground, several difficulties recur:

– comfort and functionality sometimes at odds with contemporary expectations (bathrooms, sound insulation, kitchen, utilities);

– high costs, due to the need for specialized artisans and specific materials;

– regular maintenance of roofs, woodwork, and plaster;

– heritage constraints if the hanok is listed, located in a protection perimeter, or a designated area (like parts of Bukchon or Seochon).

Successful projects, however, show it is possible to reconcile respect for the original structure and modern comfort. In a Bukchon project, for example, a demolished hanok was rebuilt on its initial footprint, retaining the Joseon style while introducing:

– courtyard facades with full-height floor-to-ceiling glazing;

– a basement housing a media lounge, wine cellar, dressing room, and garage;

– a ground floor both contemporary and rooted in traditional codes (revisited Daechong, Anbang, artisanal materials);

– a scenography designed to host an art collection ranging from ancient ceramics to contemporary works.

In a co-working office project, the architects chose to make visible the building’s different historical layers. They preserved the original structure and integrated an old metal beam into the concept. Discreet additions, like high-performance insulation and glazing, were combined with the conservation of traditional elements such as hanji (Korean paper) and artisanal techniques.

Innovating Without Betraying: Materials and Hybridization Techniques

Contemporary research explores original avenues to extend the life of hanoks or inspire new construction, for example:

– integration of secondary aluminum structures to enhance the durability of wooden parts, while benefiting from this metal’s high recyclability and thermal conductivity properties (especially for modernized ondol);

– wood-concrete-glass hybrids that adopt the logic of a central courtyard and overhanging roof, but with contemporary techniques.

These approaches remain experimental and require solving technical challenges (differential expansion, wood-metal junctions, etc.), but they point to a deeper trend: the hanok is no longer frozen; it is becoming an ecological architecture laboratory.

For an owner, the key is to rely on an architect or studio with real hanok experience, capable of navigating between heritage constraints, authority expectations, modern comfort requirements, and budgetary concerns.

Renovating an Apartment: The Art of Korean Living in a Few Dozen Square Meters

At the other end of the spectrum, the renovation of a standard apartment — often compact — constitutes the daily reality for most owners. Spaces can be modest, like this 40 m² apartment in Seoul (430 sq ft) visited in 2025: two bedrooms, a kitchen, a living room, a laundry nook. Yet, there is significant room for maneuver if one knows how to exploit the codes of modern Korean design.

Maximizing Space: Modularity and Fluidity

Land pressure in Seoul has shaped a whole repertoire of solutions to optimize small interiors:

– low furniture (beds close to the floor, low sofas, coffee tables) to clear sightlines and enhance the sense of space;

– plinths and platforms to demarcate a bedroom area without partitioning, while concealing storage;

– foldable or convertible furniture: Murphy beds, wall-mounted desks, extendable tables with integrated drawers, sofa beds, mobile kitchen islands;

– flexible partitions like textile screens or room dividers, which structure space without altering light.

For a rental apartment, it’s possible to personalize it without invasive work. The example of a 40 m² shows the use of removable backsplash coverings, adhesive LED strips, a freestanding island, and a room divider, avoiding any drilling or permanent painting. This approach preserves the property and offers great flexibility, ideal for foreign tenants or investors.

Light as a Central Material

Interiors inspired by contemporary Korean aesthetics pay meticulous attention to light:

– large windows where structure allows, or, failing that, maximizing the opening of partitions;

– sheer curtains rather than blackout, to filter but never smother natural light;

– layering of soft light sources: paper pendant lights, table lamps, diffused strips, rather than harsh ceiling lights.

In some projects, architects even integrate the concept of Wayu — literally “lying down and contemplating” — by framing views of the outside from the bed or a sofa via large windows or portholes.

Architects

Styles and Trends: From Korean Minimalism to Playful Newtro

The world of Korean design has evolved greatly, to the point of now influencing interiors worldwide. Several coexisting currents can inspire a renovation:

| Style | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Korean Minimalism | Clean spaces, furniture with rounded edges, neutral tones, pattern sobriety, maximum functionality |

| Korean-Scandi | Fusion of Scandinavian and Korean: light wood, soft textiles, natural light, plants, multifunctional furniture |

| Soft Maximalism | Muted but expressive palette (dusty pinks, sage greens, muted lavenders), texture layering, asymmetry |

| Newtro | Meeting of retro and new: 1950s–1980s influences, bright colors, geometric patterns, vintage accessories |

| Achromatic | Black, white, gray; strong contrasts, noble materials (marble, leather), geometric forms, very graphic ambiance |

| Kawaii / K-Quirk | Pop colors, references to pop culture characters (Kakao Friends, etc.), oversized volumes |

Certain emblematic realizations — like the work of Genesin Studio on Soft maximalism interiors or the Newtro projects by Minjae Kim — serve as idea banks for more modest residential renovations.

Materials and Textures: Warmth Above All

Despite the diversity of aesthetics, some constants emerge:

– generous use of wood (flooring, furniture, trim) to warm up volumes;

– introduction of natural elements: potted plants, bonsai, bamboo, wickerwork;

– presence of simple but quality textiles (linen, cotton, wool);

– surfaces that are matte rather than glossy, to avoid a cold showroom effect.

More sophisticated materials — marble, high-end leather, curved glazing — appear mainly in high-end interiors inspired by studios like Burdifilek (Hyundai Seoul) or by certain installations presented at Seoul’s major design fairs.

Renovation and Smart Home: When the House Becomes Intelligent

It’s difficult to talk about renovation in South Korea without mentioning the smart home wave. The country is one of the most advanced markets in the world in this area: estimates place the value of this sector around $5 billion in 2023, with a projection that could far exceed $18 to $23 billion by 2030, based on an annual growth rate of about 24%.

What Can Home Automation Bring to a Renovation?

In a renovated apartment or house, connected devices play on several registers:

– security: smart locks, video intercoms, IP cameras (with strong cybersecurity requirements);

– comfort: automated lighting, motorized blinds, connected speakers, domestic robots;

– energy: thermostat and heating regulation, power meters, automatic shut-off scenarios;

– health: air quality sensors, integrated ceiling purification systems, monitoring devices for the elderly.

New apartments are often equipped with basic smart functions. For existing homes, the government encourages the aftermarket via an ecosystem of compatible products and incentives to facilitate retrofitting.

Technological Landscape and Compatibility Issues

The market is dominated by local giants (Samsung, LG, telecom operators) but also attracts major global names (Google, Amazon, Apple, Schneider, Bosch, etc.). Connectivity relies mainly on Wi-Fi, accounting for over 40% of usage, while low-power cellular solutions (NB-IoT, LTE-M) are rapidly growing, driven by 5G.

A central theme is interoperability. The Matter protocol, an international standard bringing together over 500 companies, is at the heart of Korean public strategies:

– creation of a Matter accreditation center in Korea;

– strengthening of security certification procedures;

– implementation of a rewarded vulnerability reporting system (bug bounty).

For an owner renovating, it’s crucial to choose a home automation solution open enough to avoid dependency on a single brand or operator. Home automation should be conceived as a layer integrated into the architectural project, not as an isolated gadget.

Security and Data Protection: A Sensitive Subject

The omnipresence of IP cameras and other sensors in daily Korean life has also heightened vigilance regarding risks of hacking and image leaks. The government specifically plans:

– strengthened control of video-sharing platforms to prevent the broadcast of private streams;

– increased security requirements for new equipment;

– training a pool of specialists in applied cybersecurity for smart homes.

In a renovation project, especially if targeting rental use or an international audience, it becomes crucial to integrate these issues from the design stage: choice of certified devices, professional network configuration, clear policy on data collection and storage.

Renovating Small Buildings: The Lever of “Lease Planning”

Renovation doesn’t only concern individual apartments. In South Korea, many owners of small mixed-use buildings (shops on the ground floor, residences above) are turning to remodeling to maintain, or even increase, their rental income.

Why Renovate Rather Than Rebuild?

Several factors favor remodeling:

The cost of new construction in Seoul is prohibitive, reaching 12 to 14 million won per pyeong, or more.

The most cost-effective works often concern: process optimization, technological innovation, and cost reduction.

– facades and exterior finishes, which improve visual appeal;

– replacement of windows, improving acoustics and thermal insulation;

– modernization of elevators, parking, and restrooms, highly visible to users.

The Key Role of “Lease Planning”

Renovating a building only makes economic sense if you can then attract the right tenants. In South Korea, the holy grail for commercial streets is summed up by the acronym “Ol-Da-Mu”: the major brands Olive Young, Daiso, Musinsa. Attracting this type of brand assumes:

To establish a presence, major brands generally require: a well-visible facade compliant with their graphic charter, premises with dimensions (ceiling height and area) meeting their specifications, and appropriate technical amenities, particularly regarding air conditioning, electrical power, and logistic access.

Profiles like Lee Chung-mook (The Twelve PMC) or Choi Eun-young (specialist in store planning) emphasize this very early-stage integration: the renovation project must be conceived together with the leasing strategy, at the risk of ending up with a redone but partially empty building, as in the case of a “Building A” in Seoul where a strategic tenant ceased operations shortly after moving in.

For a foreign owner, renovating in South Korea adds a layer of complexity:

– language barrier: contracts, permits, technical exchanges are essentially in Korean;

– cultural codes: decision-making can be more hierarchical; unspoken expectations are more numerous, especially regarding deadlines and difficulties;

– gap in professional practices: what seems “standard” in one country may be perceived as unusual or risky in another.

The recommendations that emerge are clear:

To ensure smooth communication and avoid misunderstandings in international projects, adopt the following practices: use professional **translators/interpreters** for important meetings and contract drafting; prioritize visual aids like detailed plans, 3D renderings, and annotated sketches to clarify expectations and remove ambiguities; systematically document all decisions made via written minutes and summary emails; and involve, if possible, a **bilingual project manager** or a specialized agency accustomed to working with international clients.

On the administrative front, it’s also important to keep in mind that there is no, strictly speaking, a “freelance visa” for working as a self-builder or independent site manager. Resident visas (F-2) or business creation visas, or the use of an umbrella company structure, may be necessary if you wish to directly manage local teams as an employer.

Renovating in South Korea: Focusing on Long-Term Value

Beyond the immediate complexity — tight budgets, ambitious standards, negotiations with contractors — renovation in South Korea must be considered in terms of long-term value:

A well-designed renovation creates value on multiple levels, beyond mere aesthetic updating.

Increase in rental potential and resale price, in a market where energy performance and finish have become decisive criteria.

Tangible improvement in daily comfort: thermal, acoustic, air quality, and living space optimization.

Preservation of architectural heritage, especially for hanoks or buildings in heritage zones, contributing to safeguarding endangered heritage.

Integration of low-impact materials and efficient equipment for a low-carbon building, in line with national emission reduction goals.

In a city like Seoul, where restored hanok villages, revamped 1970s buildings, and hyper-connected towers aiming for zero energy certification coexist, each renovation is a piece of this urban puzzle. Well executed, it can be both a good investment, a tangible improvement in quality of life, and a real contribution to the country’s ecological transition.

To navigate successfully, three key focus areas stand out clearly.

– anticipate: research regulations, consult the city hall early, seek expert advice, clarify your budget;

– surround yourself: architects, contractors, legal counsel, possibly a bilingual project manager, all duly vetted;

– align: make financial goals, comfort, energy requirements, and — when relevant — heritage preservation coincide.

In this framework, renovating a property in South Korea is neither a simple decoration project nor an insurmountable obstacle course. It is a demanding, but high value-added project, provided it is approached with method, clarity, and a good understanding of local specificities.

A French business owner, around 50 years old, with a well-structured financial portfolio already in Europe, wanted to diversify part of his capital into residential real estate in South Korea to seek rental yield and exposure to the Korean won. Allocated budget: $400,000 to $600,000, without using credit.

After analyzing several markets (Seoul, Busan, Incheon), the chosen strategy was to target an apartment in a growing neighborhood like Gangnam or Songdo, combining a target gross rental yield of 8–10% (“the higher the yield, the greater the risk”) and medium-term appreciation potential, with an all-in ticket (acquisition + fees + possible refresh) of about $500,000.

The mission included: market and neighborhood selection, introduction and handover to a local network (real estate agent, lawyer, tax specialist), choice of the most suitable structure (direct ownership or local investment vehicle), and definition of a time-based diversification plan.

This type of support allows the investor to benefit from South Korean market opportunities while controlling risks (legal, tax, rental) and integrating this asset into an overall wealth strategy.

Looking for profitable real estate? Contact us for custom offers.

Disclaimer: The information provided on this website is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or professional advice. We encourage you to consult qualified experts before making any investment, real estate, or expatriation decisions. Although we strive to maintain up-to-date and accurate information, we do not guarantee the completeness, accuracy, or timeliness of the proposed content. As investment and expatriation involve risks, we disclaim any liability for potential losses or damages arising from the use of this site. Your use of this site confirms your acceptance of these terms and your understanding of the associated risks.