Published on and written by Cyril Jarnias

Published on and written by Cyril Jarnias

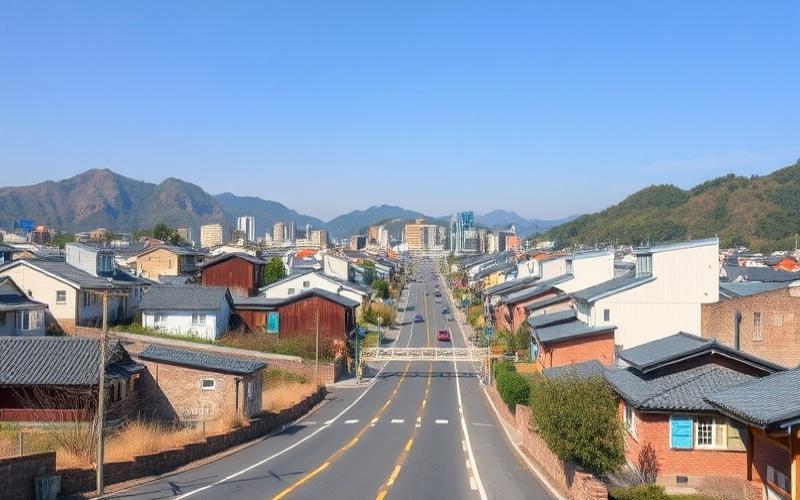

South Korea’s real estate sector is built upon a tightly interwoven web of laws, building codes, tax regulations, and tenant protection measures. Recently, restrictions directly targeting foreign purchases in the most pressured areas of the capital region have been added. For an investor, an expatriate, or even a simple tenant, understanding this legal environment has become essential to avoid missteps.

This article details all the legislation, authorities, taxes, and practices governing the South Korean real estate sector. It specifically addresses the rights of foreign investors, the legal obligations of owners and tenants, current urban planning rules, and new regulations implemented to combat speculation.

The Legal Foundation of Real Estate in South Korea

The Korean real estate framework is structured around several major laws that intersect and complement each other, each covering a part of a property’s lifecycle: land planning, construction, leasing, taxation, transfer, expropriation, etc.

The National Land Planning and Utilization Act forms the backbone of planning law. It unifies the entire territory under a single planning system, ending the historical separation between urban and non-urban areas. It determines the main zone categories (urban, agricultural, conservation, management) and establishes the principle that any development activity must comply with the applicable urban management plans.

Construction in South Korea is governed by the Building Act and its decrees, which regulate permits, safety, and inspections. The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT) steers this policy, assisted by organizations like the Korean Construction Standard Center and the Architectural Institute of Korea, the latter being responsible for developing technical standards such as the Korean Architectural Standard Specification.

Relationships between project owners, construction companies, and subcontractors fall under the Framework Act on the Construction Industry (FACI), which sets general principles for work contracts, and the Fair Transactions in Subcontracting Act, focused on protecting subcontractors from abusive clauses and payment delays. The Civil Code remains the general law governing contracts, guarantees, and liability.

Two major laws, the Housing Lease Protection Act and the Commercial Building Lease Protection Act, regulate the rental market by setting essential rules for leases.

Property ownership, land publicity, and the registration of rights are organized around the Real Estate Registration Act, while expropriation for public purposes is based on the Act on Expropriation of Land, etc. for Public Works and Compensation.

Finally, numerous sector-specific laws complement this foundation: the Foreign Investment Promotion Act and the Foreign Exchange Transactions Act for foreign flows, the REIT Act and the Financial Investment Services and Capital Markets Act for real estate funds and trusts, the Environmental Impact Assessment Act for large projects, not to mention tax laws (Income Tax Act, Inheritance and Gift Tax Act, etc.).

Urban Planning and Land Use Constraints

Access to land or a building first requires understanding the urban planning rules. In South Korea, almost every plot is subject to multiple layers of zoning, which can make reading the permitted use rights complex for the public.

Zoning and Zone Categories

The national territory is first divided into broad categories: urban zones, management zones, agricultural zones, natural environment conservation zones. Management zones are themselves subdivided into subcategories based on the permitted intensity of activity (planning management, production management, conservation management).

Within these broad categories, the core of the system is the “special-purpose area” (Yongdojiyeok), which assigns a dominant purpose (residential, commercial, industrial, etc.) to each sector. “Special-purpose districts” (Yongdojigu) can then be superimposed to add specific prescriptions: scenic districts, height-restricted sectors, heritage protection zones, etc. Finally, district unit plans (Jigudanwigyehoek) allow for micro-management of certain perimeters (building envelopes, alignments, facility placement, landscape aspects).

The extent of the regulatory web is illustrated by over 106 billion square meters covered by special zones, governed by nearly 218 different types of zones or districts created by 72 separate laws. This complexity leads to frequent overlaps, where between 5 and 6 zonings can apply to the same plot of land, generating sometimes contradictory and difficult-to-harmonize rules.

To assist citizens and investors, the ministry has established the Land Use Regulations Information System (LURIS), linked to the Korea Land Information System and legal databases, which allows for free consultation of the applicable rules plot by plot.

Green Belts and Controlling Urban Sprawl

As early as the 1970s, Korea adopted a radical tool to control the expansion of its major cities: green belts or development restriction zones around large cities. Initially created to curb chaotic urbanization and protect the environment, these belts long covered over 5,400 km², although their perimeter has been partially reduced to around 3,980 km².

Being located in a green belt zone implies strong limitations on building rights and almost systematic denials of permits for unapproved uses, with increased constraints for public projects. While these green belts preserve natural spaces near cities and provide recreational areas, they are criticized for infringing on property owners’ rights and creating rigidities in the land supply, potentially harming the competitiveness of large urban areas.

Development Approvals and Building Permits

For any project, two types of decisions are at the heart of the procedure:

– The development approval, which assesses the project’s compatibility with urban plans and the urban environment, falls under the discretionary power of the competent local authority.

– The building permit, focused on the health, safety, and technical compliance of the building, is more strictly regulated by law, although legal doctrine discusses the extent of the administration’s power.

A mechanism called “deemed authorisation” allows, when a main authorization is granted, for certain ancillary authorizations to be considered automatically granted, to spare developers an endless series of procedures.

Local authorities can also require the project initiator to bear all or part of the costs of induced infrastructure (roads, utilities, public facilities) through a financial participation system linked to the development.

Building Codes, Energy Performance, and Safety

Construction in South Korea is marked by a high level of standardization. The Architectural Institute of Korea, with ministry support, has developed a Korean Building Code (KBC) that draws heavily from American international standards (ASTM, ASHRAE, ACI) supplemented by national specifications (Korean Architectural Standard Specification).

On the energy front, the country reacted early to the 1970s oil crisis: first insulation thickness regulation in 1977, Rational Energy Utilization Act in 1979, then adoption, in 2001, of the Building Design Criteria for Energy Saving (BDCES), a mandatory energy code for buildings, updated in 2008.

The code imposes a point system to obtain the permit. The project must achieve a minimum score of 60 by combining mandatory and recommended measures.

The score is calculated by combining measures related to the building envelope, mechanical systems, electricity, and renewable energy.

To obtain its permit, the project must achieve a minimum total score of 60 points.

Energy performance certifications exist in parallel, for example for complexes with over 500 housing units.

Safety on construction sites and in buildings is governed by a combination of statutes: the Occupational Safety and Health Act, the Serious Accidents Punishment Act (which now exposes executives to prison sentences and heavy fines in case of fatal accidents), laws on fire prevention and on the installation and maintenance of firefighting systems. For large public projects, insurance covering the works and third-party liability is mandatory beyond a certain budget threshold.

Buying Property in South Korea: Titles, Registration, and Due Diligence

In South Korea, property ownership legally exists only from its registration in the land register. Signing a sales contract and paying the price alone have no transfer effect.

Acquisition Procedure and Registration

After agreeing on the price, the buyer must file an acquisition report with the city, county, or district office where the property is located, in principle within 60 days of signing (or six months for certain cases like auctions or inheritance). This report is also mandatory for foreigners, under the Act on Report on Real Estate Transactions.

Next, the buyer applies for the registration of the property transfer at the competent registry within a similar timeframe, attaching: the contract, an extract from the register, identification documents (or registration for a company), proof of payment of acquisition and stamp taxes, official forms. The land register is public and states the holder’s identity, encumbrances (mortgages, easements, registered leases), and, if applicable, the existence of a trust.

When a property is held by a trust structure or a fund, it is often the trustee bank that appears as the owner in the register, without detailed mention of the beneficial owner. This complicates identifying the ultimate owner for a third party simply consulting the register.

Trust or Fund Structure

A standard legal due diligence in Korea covers title verification, encumbrances, urban planning compliance via the land use plan certificate, existing authorizations, as well as the tax analysis of the transaction. Pollution or environmental risks remain in principle the buyer’s responsibility, unless they can prove they could not have been aware of them.

“Race Jurisdiction” Concept and Security Interests

The country operates on a first-to-file priority system. For mortgages and other security interests, the first registered is first paid in case of enforcement, making the filing date decisive. Foreign creditors wishing to take real estate security must, in addition, first file a report with a foreign exchange bank.

Real estate security takes several forms: mortgage, superficies right, registered Jeonse lease right, security trust. Banks and large investors often use trust structures: the property is transferred to a trustee who holds the title on behalf of the creditors, facilitating enforcement in case of default.

Taxes Related to Acquisition and Ownership

The purchase of a property triggers a series of mandatory taxes and fees, the main ones summarized below.

| Type of Tax / Fee | Indicative Rate (Range) | Main Tax Base |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition Tax | 1% – 12% (typically 1% – 4%) | Purchase price or market value |

| Local Education Tax (surcharge) | ≈ 20% of acquisition tax above 2% | Amount of acquisition tax |

| Special Rural Development Tax | ≈ 0.2% of value | Acquisition value |

| Stamp Duty | 50 KRW – 350,000 KRW | Sales contract |

| Registration Fees | ≈ 0.8% (0.2% – 5% depending on case) | Declared value |

| VAT (building portion only) | 10% | Value of built portion if seller is VAT-registered |

| Real Estate Agent Commission | ≈ 0.4% – 0.9% | Sale price or rental value |

In practice, some situations are particularly sensitive: the acquisition of a residential housing unit by a company is taxed at a significantly increased acquisition rate, and the purchase of a new housing unit by an individual who is already a multi-property owner can trigger ceiling rates (up to 12%) in areas designated as speculative.

The annual property tax ranges from 0.15% to 0.50% for most housing, supplemented by a national surtax, the Comprehensive Real Estate Holding Tax (CRET), when the cumulative value of properties exceeds certain thresholds (approximately 900 million won for a typical household, higher for the primary residence). In speculation zones or for luxury properties, the CRET can reach rates around 5%.

Specifics for Foreigners: Right to Acquire, Obligations, and New Restrictions

South Korea allows foreigners – individuals, companies, or foreign public entities – to hold real estate, but within an increasingly regulated framework.

General Rules for Foreign Purchasers

Outside of certain sensitive areas (military protection zones, heritage sites, ecological zones), a foreigner can acquire property in South Korea provided they: meet the specific legal requirements specified by Korean legislation.

– file a real estate transaction report within 60 days of the contract, under the Act on Report on Real Estate Transactions;

– comply with the rules of the Foreign Investment Promotion Act when indirectly acquiring property via more than 10% of the voting rights of a Korean land-holding company, or via more than 50% of the shares of a company holding land;

– comply with the Foreign Exchange Transactions Act to report the inflow of funds to a foreign exchange bank, and, if applicable, obtain a real estate registration number if they have no local registration.

Holders of permanent residency generally benefit from the same acquisition conditions as nationals. For foreign companies wishing to purchase property for commercial purposes (leasing or operation), it is generally necessary to first establish a local branch or subsidiary, particularly for tax and administrative reasons.

Rental income, capital gains from sale, and other flows are subject to the same tax regimes as for residents, with specific rates for non-residents (e.g., 22% withholding tax on real estate gains, calculated on the more favorable basis of a percentage of the gross sale price or the net gain).

The New Permit Policy for Foreign Purchases in the Capital Region

Faced with rising foreign purchases in the Seoul region and criticism of “reverse discrimination” (strict rules for Koreans, more lenient for non-residents), the government introduced an unprecedented measure in 2025: a prior permit system for residential purchases by foreigners in the metropolitan area.

This system, decided by MOLIT based on the Act on Report on Real Estate Transactions and the National Land Planning Act, applies:

The Seoul subway network serves 25 districts of the capital, 23 cities in Gyeonggi, and 7 districts of Incheon.

In these designated areas, any purchase of residential property (apartment, single-family home, villa, townhouse, multi-unit building) by a foreigner – individual, company, or foreign public entity – is subject to prior approval from the local authority.

The granting conditions are strict:

– the purchaser must move into the property within four months of purchase;

– they must reside there continuously for at least two years;

– in case of foreign financing, they must submit, within 30 days of signing the contract, a detailed financing plan outlining the foreign bank, the amount borrowed abroad, and their visa status.

Officetel (office-studio) type properties and purely commercial assets are currently excluded from the system, leaving a door open for certain arrangements.

Penalties for non-compliance are dissuasive: warning, then a fine that can reach 10% of the transaction value, repeatable in case of recidivism, and up to nullification of the contract for serious violations. If suspicions of money laundering or tax fraud arise, authorities can refer the case to foreign financial intelligence units.

Number of real estate purchases by foreigners in the Seoul region alone in 2024, a sharp increase from the 4568 transactions in 2022.

Reciprocity Question and Political Debate

The rise of Chinese buyers (over half of the foreign-owned stock, nearly 73% of foreign purchases in the capital region in the last analyzed period) has brought the issue of reciprocity to the fore. Lawmakers highlight that China imposes strong constraints on Koreans (prohibition on buying land, requirement of one year of prior residency to acquire housing), while Chinese nationals have until now enjoyed relatively open access in Korea.

Amendments are under discussion to enshrine reciprocity in law: an obligation for the government to regularly publish the state of reciprocity by country, or even conditioning certain purchase rights on equivalent treatment offered to Koreans abroad.

Jeonse and Wolse Rental Systems and Tenant Protection

It’s impossible to discuss real estate law in South Korea without mentioning the Jeonse and Wolse rental systems, which structure the residential market and have given rise to a specific legal framework.

Jeonse, Wolse, Ban-jeonse: How Leases Work

Jeonse is a lease based on a large lump-sum deposit paid to the owner at the start of the contract, in lieu of monthly rent. The amount of this deposit varies greatly by market but is most often between 50% and 80% of the property’s value, rising to 70%–90% in the most expensive neighborhoods of Seoul. The tenant then pays no monthly rent, and the owner returns the deposit at the end of the lease, typically two years, if no damage is found.

Wolse corresponds to a more classic scheme: a security deposit, usually between 10 and 20 times the monthly rent (with great variability), and rent paid each month. There is an inverse relationship between deposit amount and rent: the higher the deposit, the more the rent can be negotiated downward.

Ban-jeonse is a hybrid Korean lease formula. It requires a security deposit higher than Wolse (classic monthly rent) but less than Jeonse (lease with large deposit and no monthly rent). In exchange for this intermediate deposit, the monthly rent to be paid is reduced.

These mechanisms are explained by the country’s financial history: absence of mass mortgage credit in the 1960s-1970s, need for private financing for owners, soaring land prices. Jeonse acts as a quasi-non-interest-bearing loan to the lessor.

Rights and Obligations under the Housing Lease Protection Act

The Housing Lease Protection Act regulates these contracts and provides a base of rights for tenants. The minimum legal term for residential leases is two years, but a 2020 reform strengthened the renewal right: a tenant can request a two-year extension, provided they make their request between six and two months before expiration. The landlord can only refuse for specific reasons, e.g., if they plan to move in themselves or house a close relative, or in case of serious breaches by the tenant (false documents, unauthorized subletting, significant damage).

The maximum percentage increase in rent or security deposit during the legal renewal of a lease.

The most crucial protection concerns the deposit. To secure their right to reimbursement, the tenant must:

– declare their move-in (전입신고) at the local community center within two weeks;

– obtain a fixed-date stamp (확정일자) on the lease contract.

This dual action gives the tenant enforceability and a priority right over part of the sale proceeds in case of the owner’s seizure or bankruptcy. In Seoul, the law recognizes a priority up to 55 million won for small deposits, with some limitations if this amount exceeds half the property’s value.

Additionally, the tenant can, with the landlord’s agreement, register a specific Jeonse right in the land register (전세설정). In case of the owner’s default, they can also request a leasehold right registration order (임차권등기명령) to retain their right to reimbursement even after vacating the premises.

The security deposit (Jeonse) can be covered by specific insurance, managed for example by the Korea Housing & Urban Guarantee Corporation (HUG). Under certain conditions related to the property value and deposit amount, this insurance compensates the tenant in case of default by the owner.

Risks, Frauds, and Regulatory Responses

Rising prices, falling interest rates, and increasing debt among some landlords have fostered Jeonse frauds: owners over-mortgaging their properties and unable to return the deposit, unscrupulous intermediaries pushing tenants towards properties already saturated with debt, etc. A major scandal around an operator nicknamed the “Villa King” highlighted the scale of these risks between 2022 and 2023.

The legal framework attempts to respond through several levers: facilitation of recourse via small claims courts (up to 20 million won), strengthened information obligations for real estate agents, extension of deposit insurance ceilings, mediation by specialized conciliation committees.

Tenants, both Korean and foreign, are strongly encouraged to check the land register extract (등기부 등본) before signing, to ensure the contract is properly registered, and to go through a certified agent duly insured and registered with the district administration.

Real Estate Taxation: Acquisition, Holding, Transfer, and Rental Income

Korean real estate taxation is sophisticated and often heavy, particularly for multi-property owners and corporate structures dedicated to residential property. It clearly distinguishes three moments: purchase, holding, and sale, to which is added the taxation of rental income.

Purchase Taxes

For an individual purchasing housing, the acquisition tax is usually between 1% and 3% of the value but can climb to 12% for an investor already owning multiple homes in over-concentration control zones. A company purchasing residential housing is immediately taxed at an increased rate (e.g., 12%). Local surtaxes (special rural tax, education tax) add to the bill, alongside registration fees, stamp duty, and agent commission.

For a finer breakdown, some typical cases can be illustrated:

| Acquisition Situation | Indicative Acquisition Tax Rate (excluding surtaxes) |

|---|---|

| Purchase of housing by an individual (1st property) | ≈ 1% – 3% |

| Inheritance | ≈ 2.8% (2.3% for agricultural land) |

| Gift (excluding non-profit organizations) | ≈ 3.5% |

| Acquisition of housing by a company | ≈ 12% |

To this may be added VAT on the built portion if the seller is a “business operator” under the VAT law (common for developers), while the land portion remains exempt.

Recurrent Holding Taxes

Owners pay a local property tax annually, calculated on the taxable value (generally lower than market value), supplemented by a local education surtax. Rates vary by property type (land, building, residential, industrial) and location. Factories in over-concentration zones may see their tax multiplied for several years.

Beyond a threshold of approximately 900 million won, a progressive national tax (CRET) of 0.5% to 5% applies. Its calculation was recently tightened for companies, with the removal of certain allowances.

Capital Gains and Taxation of Profits

Real estate capital gains are taxed as separate income, with very progressive rates and punitive regimes for short-term speculation. The basic formula for calculating gain is:

To determine the gain or loss realized from the sale of a property, the formula is applied: Selling price – (acquisition cost + necessary expenses) – deductions. For example, for an apartment bought for 200,000€ with 10,000€ in notary fees and sold for 300,000€, assuming a standard deduction of 1,000€, the calculation would be: 300,000 – (200,000 + 10,000) – 1,000 = 89,000€ of taxable gain.

A basic deduction of 2.5 million won per year of ownership applies, along with a special deduction for long-term holding increasing with duration (10% from 3 years, up to 30% after more than 10 years). But for properties held less than two years, rates can go very high: up to 70% for a holding period of less than one year, about 60% for a period between one and two years, before falling back to the normal scale (6% to 45%) beyond two years.

Multi-property owners are also subject to additional surtaxes of 20 to 30 percentage points when selling a residence under certain conditions, and areas designated as speculative entail increased charges. For non-residents, a flat-rate mechanism taxes the gain at the lesser of 11% of the gross sale price or 22% of the net gain (rate including local surtaxes).

The sale of your primary residence can benefit from a capital gains tax exemption under the ‘1 household – 1 home’ rule. To benefit, you must have owned and occupied the home for at least two years. Gains are fully exempt up to a sale price of approximately 1.2 billion won. Only the portion of the gain exceeding this value is taxable.

Rental Income and Structures for Foreign Investors

Income from leasing is taxed as ordinary income for individuals, following the progressive scale (6% to 45% plus 10% local surtax). For small landlords, there are simplified regimes where an expense allowance is applied (between 20% and over 60% of gross income, depending on the property type and total amount).

Foreign investors can structure their investments via limited liability companies (YooHan hoesa). This type of vehicle, which mainly requires tax registration, allows for risk isolation and, in some cases, to benefit from a flat tax rate (around 22% on certain passive income), subject to the applicable tax treaty.

Transfer, Inheritance, and Gifts of Real Estate

South Korea applies one of the highest inheritance and gift tax regimes in the world, which has direct implications for the holding and transfer of real estate assets.

Scope of the Inheritance and Gift Tax Act

The Inheritance Tax and Gift Tax Act applies to any transfer of assets upon death or by gift. For a resident decedent, the tax base includes all worldwide assets; for a non-resident, only assets located in Korea are taxable. Heirs and legatees are jointly liable for payment of the tax up to the value received.

Property tax rates are strongly progressive, ranging from 10% to 50% according to a bracket scale. Numerous allowances are provided (basic allowance, for spouse, children, elderly or disabled persons). However, exemption thresholds remain modest compared to the high real estate prices in the Seoul metropolitan area.

Gifts are taxed under the same scale, with specific, lower allowances for spouses and children. Furthermore, assets gifted shortly before death (3 to 5 years) are reintegrated into the inheritance tax base, limiting last-minute transmission strategies.

Civil Rights of Heirs and Succession of Real Estate

Under Korean civil law, certain heirs (descendants, spouse, ascendants, siblings) benefit from an inalienable statutory share (forced heirship). Even in the presence of a will, they can claim a minimum percentage of their theoretical share. This statutory share limits the freedom to transfer real estate assets to whomever one wishes, especially when children from multiple unions are present.

Heirs inherit both the assets and the debts of the decedent. Faced with significant liabilities, they must choose between renouncing the succession or accepting it up to the net asset value. Renunciation must be made within three months of learning of the death and requires a declaration before the family court.

For foreigners, a private international law statute (Private International Act) provides in principle that the decedent’s national law governs their succession, but the location of real estate assets in Korea often implies the application of Korean rules at least for registration and land publicity matters. In practice, cross-border successions involving Korean real estate are complex and require close coordination between lawyers in the country of origin and local counsel.

Specific Construction Rules, Construction Contracts, and Disputes

Beyond ownership and leasing aspects, Korean real estate is governed by a whole series of rules touching on construction contracts, guarantees, liability, and dispute resolution.

Construction Contracts and Subcontractor Protections

The Framework Act on the Construction Industry establishes principles of fairness and good faith in the negotiation and performance of work contracts. It notably imposes an obligation to negotiate fairly (Article 22) and provides for the possibility of nullifying certain clauses deemed excessively unbalanced.

The Fair Transactions in Subcontracting Act goes further in protecting subcontractors: prohibition of “unfair special agreements”, obligation to settle payments within 15 days of receiving a progress payment from the project owner, payment guarantee for subcontractors in case of the main contractor’s bankruptcy.

Construction work is subject to warranties for defects of 1 to 10 years depending on the nature of the works, under the FACI. Contracts typically provide for delay penalties (often between 0.05% and 0.3% of the amount per day) and overall liability caps expressed as a percentage of the contract price.

Public projects use standardized general contract conditions, made mandatory, while private operations can rely on models disseminated by the ministry. International contracts of the FIDIC type are sometimes used, subject to adaptations to Korean law.

Insurance, Security, and Site Risks

Large projects require specific insurance policies, the most common being “Contractor’s All Risks” (CAR) insurance, supplemented by liability insurance for work accidents. For large public contracts exceeding 20 billion won, works and civil liability coverage is legally mandated.

Percentage of the contract typically required as a performance bond in the private sector.

Disputes related to construction can be submitted to ordinary courts, but there are also Construction and Architectural Dispute Mediation Committees established by the framework acts, as well as the possibility of recourse to arbitration administered by the Korean Commercial Arbitration Board (KCAB).

Expropriation and Major Infrastructure Projects

When the state or a local authority launches a public utility infrastructure project (road, railway line, major facility), the Act on Expropriation of Land, etc. for Public Works allows compelling owners to cede their properties in exchange for compensation.

Expropriation begins with a public announcement and notification to owners, followed by a negotiation phase. If disagreement persists on the price, an appeal can be filed with the Central Expropriation Committee, which makes its decision on the compensation amount within three to four months. The transfer of ownership becomes effective on the date set by the committee, even if the owner later decides to challenge the decision in court.

Major projects of national scope (high-speed rail lines, airports, highways) remain, in their overall design, under the competence of the central government, even if implementation is often coordinated with the affected local authorities.

Recent Trends and Reform Issues

The Korean real estate regulatory landscape is in constant motion. Several trends are emerging.

First, a regulatory inflation in the construction sector: nearly 300 bills or amendments touching on construction were submitted during a single legislative term, compared to less than 70 aimed at relaxing or removing rules. To build a multi-unit building, a developer must comply with nearly 300 different regulations.

In parallel, political signals announce the will to rationalize this normative structure, with some authorities mentioning the removal of “unnecessary regulations” to fluidify the market.

A bill aiming to establish an unlimited renewal right and regional rent caps to secure precarious households was withdrawn facing hostility from sector players, for fear of further freezing the already tight Jeonse market.

Finally, the question of the role of foreign capital in housing crystallizes tensions. The shift towards a permit system for foreign purchases in the capital region fits into a global trend (Canada, Australia, Singapore, several U.S. states) of restricting or over-taxing non-resident investors. However, experts point out that such measures have rarely solved the core problem of housing affordability, often linked to insufficient supply and internal factors rather than foreign flows alone.

—

Investing or finding housing in South Korea requires mastering a sophisticated legal environment. It is crucial to be informed about dense urban planning rules, heavy taxation, atypical rental systems, and new constraints specific to foreigners to seize opportunities with peace of mind.

A French entrepreneur around 50 years old, with a well-structured financial portfolio already in Europe, wanted to diversify part of his capital into residential real estate in South Korea to seek rental yield and exposure to the Korean won. Allocated budget: $400,000 to $600,000, without using credit.

After analyzing several markets (Seoul, Incheon, Busan), the chosen strategy was to target an apartment in a fast-growing urban neighborhood like Gangnam or Songdo, combining a target gross rental yield of around 7–8% – the higher the yield, the greater the risk – and medium-term appreciation potential, with an all-in ticket (acquisition + fees + potential refurbishments) of about $500,000. The mission included: selection of the city and neighborhood, connection with a local network (agency, lawyer, tax advisor), choice of the most suitable structure for a non-resident, and development of a diversified wealth management plan over time.

Looking for profitable real estate? Contact us for custom offers.

Disclaimer: The information provided on this website is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or professional advice. We encourage you to consult qualified experts before making any investment, real estate, or expatriation decisions. Although we strive to maintain up-to-date and accurate information, we do not guarantee the completeness, accuracy, or timeliness of the proposed content. As investment and expatriation involve risks, we disclaim any liability for potential losses or damages arising from the use of this site. Your use of this site confirms your acceptance of these terms and your understanding of the associated risks.